My father and I were discussing increasing construction and diminishing public space in Beirut and, in particular, access to the seafront in the Manara neighbourhood. Suddenly, he asked if I had ever noticed al-Ba`sa (in English: The Grudge). “Which grudge?” I answered. “I thought we were speaking about buildings.” The "Grudge,” he tells me, “is a house—or maybe a wall—built to block the sea view of some residents. It is a building located in Beirut’s Manara area, just by the old lighthouse. It was constructed in the mid-1900s and might just be the thinnest inhabitable building in the world.” I was slightly taken aback by the name, and the fact that I—an urban planner and architect who often walked in the area—had no clue what my father was talking about. Rather than ask for more information and appear clueless, I decided to investigate the so-called “Grudge” myself at the first opportunity.

Finding the Grudge

The destruction of Beirut during the war, the post-war reconstruction efforts, and the current real-estate boom drastically changed the city’s housing stock. Therefore, my hopes of learning more about The Grudge and its history seemed nominal. It has become common practice in the city to destroy structures and replace them with high-end housing. The whole situation is made even more difficult by the city’s building and zoning laws, which allow for taller buildings around the city. These changes have been accompanied by weak action plans and inefficient public policies to preserve the urban fabric. Both policies and laws were designed to invite investors to destroy existing structures and build newer, grander ones. The private sector was quick to comply with these policies, with the outcome being the changing of the city’s social fabric. Old buildings are being replaced with new ones catering to the high-income strata, speeding up the gentrification of the city. Against this background, it was safe to presume that this old deserted building, in the steadily developing Manara neighbourhood, would soon be destroyed. The Beiruti real estate prices were on the rise, and the plot on which it stands, redeveloped.

Curious to find out more about The Grudge, I walked around in the area, asking people I met along the way about the building. After having been sent in almost every possible direction, and finally down to the Corniche, I walked back up the hill to the old lighthouse. Suddenly, I spotted right in front of me a 14-metre-high edge, no wider than one metre! I had passed it many times before, had even looked at the facade, thinking, “What an intriguing, abandoned low-rise building with a sea view.” Mesmerised by its “fake” facade, which at first glance made the house appear wide enough to be inhabitable, I approached the concierge of the building next door to inquire further. “Yes, I know. It’s shocking,” he said, before I had even finished my question. “It’s a wall. But people used to live in it. Is this what you were looking for?” The concierge continued to explain that this wall is the most expensive real estate wall in Lebanon, before admitting that he was actually relatively new to the area and didn’t know more about it. He suggested I return during the week and talk to a mechanic whose shop is located on the ground floor of the building.

[The "Grudge" seen from its widest edge, looking west. The building to the left is the German school in Beirut. Image by author.]

Understanding the Grudge

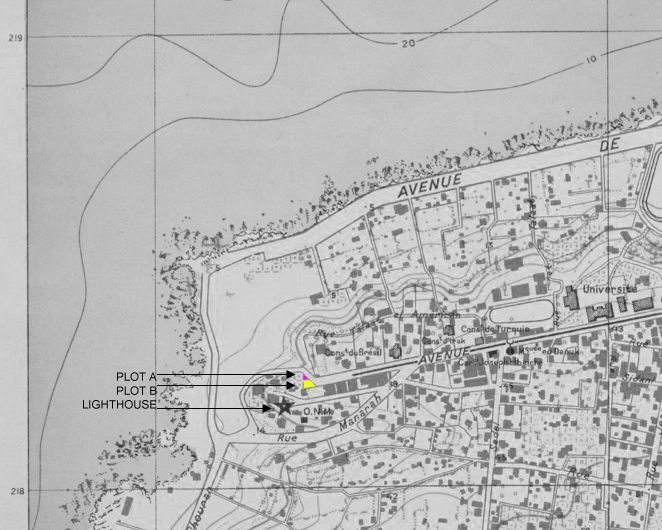

At home that evening, I tried to trace the evolution of The Grudge from the various maps I have of Beirut. The size of the plot is indeed very small and narrow. A map from the 1920s shows a road cutting right through the area, while one from 1936 outlines how it was divided into several parts, with a small corner plot where The Grudge sits today. These multiple planning layers, which include road infrastructure developments, setbacks for other forms of public infrastructure, and plot divisions according to inheritances, often create several such small, “unusable” private plots that remain abandoned in overly dense cities.

Intrigued by this habitable wall disguised as a building, I returned to my father with questions. “Why is it called “Grudge,” and why and how was it built?” I asked him. My father then started recounting an urban myth. “There were two brothers who each inherited a plot. Let’s call them plot A and plot B. Unable to agree on how to develop the two parts, since plot B was partly reclaimed by road infrastructure, the owner of plot B decided to develop the minuscule piece of land on his own. That way, he hoped that his building would block the brother’s view of the sea so that the value of his land would decrease.”

[Location map showing plot A (where the "Grudge" was built, and adjacent plot B, and the nearby lighthouse (manara). Old map of Beirut, adapted by author. ]

So, it turns out that The Grudge, an extremely narrow building standing on a mere 120-square-meter piece of land, is actually the physical embodiment of a grudge between two brothers. Ironically, two slightly more loyal brothers, architects Salah and Fawzi Itani, built the thin house. While the facade, with its proportional windows and balconies, seems to be hiding a normal building, a look at one of the flanks reveals a different story: the building was constructed to serve as a wall, blocking what would have been a million-dollar view.

According to residents in the neighborhood, The Grudge was built in 1954. The livable wall ranges in depth from four meters at its widest, to sixty centimeters—the depth of a closet—at its slimmest. What is even more exciting is that the building, it turns out, is one of the few buildings in Beirut that will be saved from destruction by the law. Although it is not listed as a heritage building, and therefore not protected by the bill protecting such buildings, the plot on which The Grudge stands cannot be developed under the city’s current building and zoning laws. According to those laws, no new structure may be built in its place, even if the house is demolished, because the plot has an area that is smaller than what you are allowed to build on. Therefore, leaving The Grudge the way it stands is more profitable for its owners than tearing it down, as they would not be able to sell the land to developers.

.jpg)

[The "Grudge" seen from its thinnest edge, looking east. Image by author.]

Living in the Grudge

On my next trip to the building, I met the mechanic who the concierge had told me about. He is a busy father who works as a fisherman and runs his workshop in order to put his daughters through college. He shares what he knows about The Grudge. “The building is unique and blends into the city much more than the high-rises being developed around it. This is Beirut, not New York,” he says. “I am from here, and these fast changes and the privatization of the city are not acceptable to me. I can hardly fish in the sea anymore because of the private claims to the seashore. I hope they won’t bring this building down too. But I don’t think they will. It is not in their interest.” Having spent the last seventeen years working in the shop as a mechanic, he reluctantly acknowledges that he may have to leave it one day. Currently, he rents it unofficially at a very low price from the owners in exchange for keeping a watchful eye on the deserted building. He also told me that the house is well known in the city for several reasons. “Before the war, people called it The Queen Mary, or The Ship,” he said. Upon seeing my puzzled expression, he asked: “Haven’t you seen the roof yet?”

Soon, I found myself inside the building, heading for the roof. The stairwell and entrance are wide enough to enter comfortably. “I am inside the wall,” I thought to myself, excited. I discovered that each floor is divided into two apartments. The first begins with a kitchen, followed by a series of rooms that sequentially diminish in size as they become more private. As you continue into the apartment, the space gets narrower with each room, until you reach a very tight area. The apartment ends at a bedroom, followed by a long fifty-centimeter walk-in closet. The roof clearly shows the footprint of the building and highlights its narrowing effect.

[A view from the roof of the "Grudge" building. Image by author.]

The second apartment on the wider side of the site is also connected by a corridor that cuts through each room. The quality of light in the space and the sea view from the rooms make it seem large enough for a resident to forget that he or she lives in what is essentially a wall. The high ceilings and windows allow ample light to flow in, which helps to create a sense of spaciousness. Each room inside The Grudge has two sources of light; one towards the brother’s plot—today, the German school, with The Grudge blocking its view—and the other from the front, towards the Mediterranean with its beautiful, uninterrupted view of the sea.

[Interior view of the "Grudge." Image by author.]

After the tour, I returned to the mechanic and told him that while I was excited about the building’s similarity to a wall, I saw no resemblance to a ship even after having seen the roof. He then started pointing to the facade, showing me several openings and the corner curve. Annoyed by my skepticism, he told me that one day, as he worked away in his shop, he saw an old man on the other side of the road getting out of his car and looking amusedly at the building. Curious, the mechanic crossed the street and asked the man if he was lost. The man, it turned out, was Fawzi Itani, one of the architects who had designed the building. Itani, the mechanic tells me, explained the idea of the ship, The Queen Mary. He also told him that the building was built quickly because of problems between the brothers. I smiled knowingly, telling him I had heard about the brothers and their quarrel about the plots. “The building used to be beautiful,” the mechanic continued wistfully. “But during the war, it became filthy. One apartment was used as a brothel, and the rest were occupied by an extended family seeking refuge. In those years it was yellowish, never pink. It was recently painted pink by the developers of nearby plots, who want to beautify the surroundings of their million dollar projects,” he added. “Did you see how narrow it gets at the end?” he asked excitedly. I nodded and thanked him for his time and for allowing me to access the site.

Urban Forms of Production

The systems that produce our urban environment are usually most evident in these abandoned residual spaces. These spaces are created as “leftovers” in a process of policy development at the macro-scale. They include changes in zoning laws, infrastructure planning, and the development of generic building laws. In addition, these abandoned plots may be created from private macro-scale deals and remain in the city as privately owned and abandoned residual spaces as a result of land deals, the carving up of larger sites, or the slicing through of plots according to inheritance laws. These “awkward” residual spaces, which are privately owned but abandoned in a dense city with no breathing space, usually result in a feeling of absence or ambivalence. While they are usually orphaned pieces of land, the manner in which they have come about is fascinating. The Grudge today is a testament that generic building laws that do not permit unique re-use of these spaces are obstructing fruitful opportunities. The building therefore is a tribute to the failure of planners to realize the effects of their macro-scale interventions in socio-political, economic, and built localities. As for this unique structure, which continues to exist grudgingly and also defiantly in one of Beirut’s most prime locations, only time will tell what will become of it.

[This essay is reproduced by permission from the edited volume: Collectifs Mashallah and AMI, Beirut Re-Collected (2014) Beirut: Tamyras. The book is also available in French as Beyrouth, chroniques et détours.]